Interview with Kim Sandara

VisArts Bresler Resident Artist

interviewed by Iona Nave Griesmann.

Kim Sandara is a queer, Laotian/Vietnamese artist based in Northern Virginia. In 2016 she graduated from the Maryland Institute College of Art with a BFA in General Fine Arts. She makes stream-of-consciousness paintings which interpret sounds into visuals. She is currently working on a graphic novel on her coming out story and a painting series advocating for the funding to remove bombs from Laos. Although Kim’s illustrations are often narrative and her paintings are abstract, her overall focus is to encourage empathy, wonder and self-reflection.

You state in your artist bio that one of your focuses during this residency is exploring your experiences as a Lao American woman. Have you discovered anything new in your practice while making work about those experiences?

As I researched more on the Vietnam war and The Secret Wars, I gradually got angry about my identity, and the history I felt was hidden away from me as an American, and as a Lao person. I was trying to find my voice in sharing this history. I knew I couldn’t just start making landscapes about Laos in a land I’ve never been in. I decided to go down the route of my fine art practice being more geared towards music, and I was trying to think about where music, and my Lao identity intersected.

As a child I didn’t like Lao music at all. It was kind of pushed upon me, I only heard one type of genre. My dad’s favorite music is from the 50’s before the war. It’s all very slow and sleepy to me. In my exploration of Lao music, I’ve been trying to figure out what other genres and artists are out there in the Lao diaspora. It still seems very young. There’s a huge music gap where there’s old music from the 50’s in Laos, and then suddenly there’s young native and displaced Lao people making a lot of different work.

For me that’s been really big, because I feel like it’s given me a way to be a Lao American in my own way instead of having to fit this mold of what my dad presented to me. That work has helped mold how I see myself. Through that empowerment, I came up with the 270 Million Project. I am creating one painting per million bombs dropped on Laos during the Vietnam and Secret Wars. I am channeling all my processing of such a violent history and desire to contribute positively in this work. Through the sales of the project, I will be donating money to Legacies of War, a non profit that advocates for funding from Congress to remove the bombs from Laos. Some of the money will also go to COPE, a Lao non-profit which currently helps bomb accident survivors both in physical therapy, and mental therapy.

![image1[5423]](/x/lc-content/uploads/2020/10/image15423.jpeg)

#1 of 270 Ink paintings in the 270 Million Project, raising money for the removal of Bombs in Lao, and relief aid for bombing survivors. Find more about this series: https://www.kimsandara.com/270millionproject

As an artist you are incredibly well rounded in different styles and mediums, working in projects from stop motion, comics, illustrations, to more recently felting . How were you able to become so well versed in so many different styles and mediums?

I’m curious about a lot of different things. That’s why I changed my major in MICA (Maryland Institute College of Art) from Illustration to General Fine Arts, because I wanted to do a little bit of everything. It seems like fine arts is just painting and sculpting, but I was doing painting, illustration, graphic design and animation. I continued that mindset through life, learning what peaks your interest.

I think being well rounded is also a survival-mode immigrant mentality. You have to be willing to do different kinds of jobs to keep yourself afloat. The skills I have do not always make me money, but it does help me mentally. Being able to do a lot of different things helps keep myself interested. The felting definitely was a weird hidden talent.

Find more about Kim Sandara’s felt work at: https://www.instagram.com/kimthediamond/

I try to capitalize where I can to keep myself afloat and to expand my practice. But I never do it from a standpoint of “I’m going to learn this to make money,” it’s always something like “Oh I’ve learned this, I can make money off of it!”. I have to enjoy it first before I decide to capitalize or do commissions, because what’s the point of working for yourself if you’re not enjoying it?

How did you discover your process of interpreting sound into visual abstractions? did this style branch off from a previous style, or was it more spontaneous and natural?

I think music has always affected me in a way that I couldn’t quite express yet. I’m such a daydreamer, and I always get very wrapped up into what I am listening to, so I think that was always in me.

I really found this way of creating in college. I had a teacher who was trying a bunch of different things to poke at the freshman, to see what kinds of things were within you. One of his assignments was to bring a lot of paper to a six hour long studio day, and then to listen to music and draw to see if anything came from it. For some people it was a very boring day. For me, I was really invigorated! It felt good to use my body as a vessel, to have these subconscious reactions to sound that I never freely let myself do before. Letting go felt good, and I wanted to see where it would go. I actually finished drawing all over a fifty foot scroll of paper, and it was such an interesting experiment. It became a little mural, and I was like, “wow! I have a lot of energy for this!”

I had to downsize coming home after college because there wasn’t much space, but it also led me to create more detailed work with more brush variations. In the transition, I figured out how to make landscapes and little universes within the spaces I do have.

![image2[5424]](/x/lc-content/uploads/2020/10/image25424.jpeg)

Sixteen Feet Glow, 200″x12″, Glow-in-the-dark Spray Paint, acrylic paint, ink on un-stretch canvas, September 2019

Do the patterns and colors on paper represent images you see in your head? Or are they instead, more visual manifestations of your emotions/thoughts?

I feel they’re both right. It’s kind of intuitive, but sometimes I feel that the sounds are colors, and that it’s not anything I can tell it to be.

I can’t say that happens all the time though. Sometimes I just want to make a painting and I’m not inspired but I try anyway. I think that is more associative, where I’m subconsciously reading into a song or a sound, and associating that feeling with a color, as opposed to being more immediate. Both of those things happen.

As a child growing up, what were some of the conflicts you faced, existing in both the spaces of being queer, and a child of Lao/Vietnamese immigrant parents?

I vaguely knew that my parents had to leave because of the war, that Laos was not a wealthy nation, and that there were bombs there, but I had no idea how many there were. I just heard that I should stay in America and wait for them to clear before I went back. I really thought it was a smaller issue than what it actually is because my parents downplayed it. They probably downplayed it because of their own trauma, and their desire not to look back into the past, because it was traumatic for my family to come here in different paths.

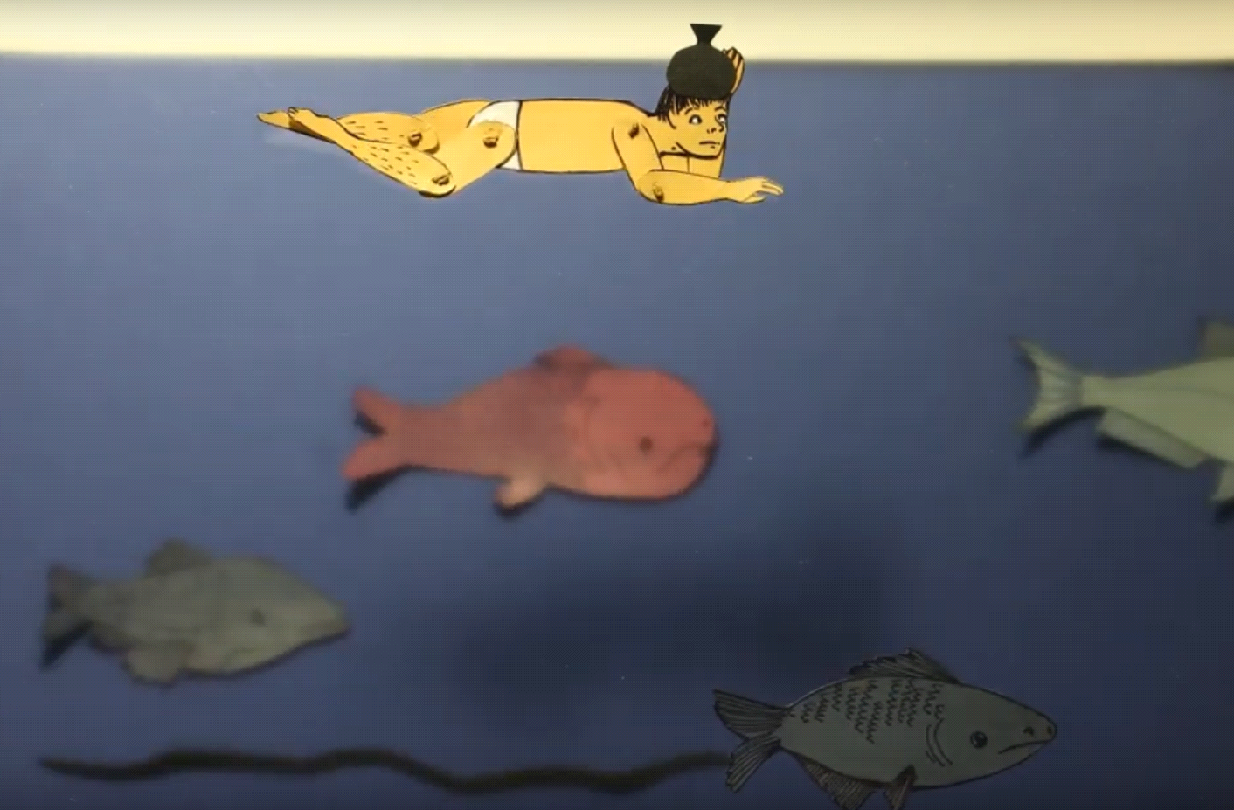

My dad didn’t even come with his family. He had eight siblings and they all went individually. Because everyone had a different timeline, everyone had different privileges and opportunities. Some swam across the Mekong River, and some just bought a plane ticket. My mom traveled with her whole family, so that situation was a bit scarier. They escaped together by hiding money from soldiers to sneakily pay a boatman to get them to a Thai refugee camp. I had never even heard about the refugee camps until I was probably twenty four or twenty five, last year when I was making that animation on Origins of Kin and Kang. There were memories my parents never spoke of because it was probably hard for them, and I’ve never asked them in high detail about it.

( 2019 animation short, Origins of Kin and Kang. Kim Sandara’s father is depicted disguising himself as floating trash to avoid soldiers while swimming across the Mekong river. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=00DJ6hx1jLg. )

I had to have a sense of humor growing up. I was conflicted about having to explain myself everytime someone would say, “where are you from but like, where are you really from?” Nobody knowing about Laos was annoying. No one knew where I was from, or why I was here. I didn’t even really know why I was here either.

I feel there’s a big Vietnamese population in this area, and I don’t even think that many Vietnemese people know the details of their own history, the same way I didn’t know growing up. I’m part Vietnemese, so it was kind of strange. I didn’t feel like I belonged in the Vietnemese community because I didn’t grow up with Viet culture much. I grew up with a lot of Lao culture, but there’s no Lao people around, so does the culture exist? This is what I always felt growing up.

And then being Queer felt like a whole other thing that I wasn’t supposed to be. Even when I made Queer friends I didnt feel comfortable, because they were just gay, or thats just how they identified it. I didn’t really know who I was because I just kept going back and forth and was like, “am I indecisive? Do I not know what I want?”. But I do have to say I did think a lot about marriage growing up, and a lot about family, wanting that sense of home. I was just talking to a friend yesterday about how she and I have always felt this sense of loss about home throughout our whole lives, and wondered why that was. She said it made sense for anyone in a diaspora. We didn’t grow up in a village community where our parents knew everyone and felt supported.

A lot of children of immigrants grow up feeling like they need to protect their parents from the world, because the world is not kind to them, especially if English isn’t their first language. As a child you feel the need to know English really well to be able to help them on things like paperwork, and big stuff that seven year olds shouldn’t have to do. I also felt I had to protect them from my queer identity because it would be unfortunate for our family to have the burden of me. There wasn’t a bisexual community or representation in the media, so I didn’t really have any space to see myself. That felt really hard on both fronts.

How were you able to use art to come to terms with this intersectionality of identity?

When I was younger I always felt like these two identities should be something hidden. It was just a suppression of emotions to fit in and assimilate. That’s probably why I thought about marriage a lot. I hoped that I could fit into the heteronormative setting so I could be safe, because I didn’t feel safe all my life within myself, my identity, and with my parents. I felt invisible and that I was supposed to be invisible, or that I was supposed to be the helper and not the helped.

It feels good to be an artist looking back at this past and realizing it makes me special because it’s a unique experience. Even if there is just a small population of Queer Lao people, which I doubt, it’s great to see that I can own it now and feel proud of it. There’s still internal things that are being worked out like internalized racism and homophobia, but it feels good to be loud about it instead of thinking that it’s just a funny thing about my life that I have to deal with.

Can you share with us a little bit more about your upcoming comic, the Origins of Kin and Kang? What are some of your struggles and learning experiences you choose to address in this novel?

I started The Origins of Kin and Kang in the summer of 2017. I sat down with myself, and really had to do some soul searching and think about why I was making art. I had recently come out of school, lost and figuring out what I was supposed to do in this world.

I didn’t even really know what my voice was as an artist yet. I was still developing my music paintings and something about that felt Queer, but I didn’t know how to express it until I learned about Queer Abstraction. This is an abstract way of working where Queer people create spaces for themselves in an escapist mentality because there are not enough spaces for us in reality.

The history of abstract expressionism is very white and very male. That’s not the only narrative there is out there for that kind of work. Even internationally, the same kind of work was being done in Japan during the 50’s, while they were coping with the finishing of World War II. It was abstract expressionism used to cope with the massive bombing of a country. It’s definitely a different angle than what Jackson Pollock was expressing. It upsets me that Abstract Expressionism is not viewed in the lens of healing that it can be used for in other populations, aside from white, straight passing, cisgender men.

Quarantine Queer/Trans Dance Party, 9″x12″, Gouache, Marker, Pen on Paper, April 2020

In my escapism, I turned to LGBTQ+ media for comfort. I wanted to hear stories where my identity is normalized but a lot of these movies are crappy. They don’t have great story lines, they feel like they are directed by straight men, it’s always sad and longing, and they never end up happy, or if it’s happy it’s comical. I was very inflamed about that. I wanted to see more Queer media that was POC centric and realistic, that didn’t have to be about a love story even, it could just be about figuring yourself out. So I threw all these things together in a pot, stirred it and said “okay well I did learn illustration, and I do like graphic novel formats.” Making abstract work was one way I liked thinking about this, but I also wanted a more accessible way to reach an audience, the way I watch movies and read books.

I had these characters Kin and Kang ever since I was in high school. I made up these two personas to talk to when I was upset and struggling, because I had a hard time opening up to friends. I had so much internal stuff I needed to deal with, so I talked to myself a lot. My imaginary alter egos Kin and Kang helped me get out of the closet. I wanted imaginary friends who wouldn’t judge me, and who were me. I wanted to accept myself. Their stories manifested in a way where I experience something, and then try to process it to myself through a story, to make sense of what’s happening. I did that all through high school and pretty much all of college too. I always thought I would share it one day when I was ready.

There’s this fantastical story that’s told within the book, so its not just about sexuality and sad teenagers, but how Queer people escape. I think how Queer people escape is really fascinating. I think everyone does it in a different way, and so many of those stories are not told. I would rather read books and watch movies that are fantastical dealing with queerness, than to watch the same love story that ends in the same way. I had to make it, because I hadn’t seen something like this before.

It’s also my genuine way to give back to the community. That’s how I also got the idea of donating a percentage of book sales to an LGBTQ+ non profit. LGBTQ+ youth homelessness problem stands out to me the most. 40% of homeless youth are in the LGBTQ+ community. I’ve also recently been more drawn to The Trevor Project, helping LGBTQ+ lives that are depressed and don’t have anyone to talk to. It’s definitely relevant to my story.

I haven’t figured out how to route the money yet, but that’s what I’m doing in 2021. I’m excited to get in touch with nonprofits. I think what keeps up my drive is that my own processing of experiences and feelings will help someone else process theirs. I believe in the power of storytelling.

I haven’t figured out how to route the money yet, but that’s what I’m doing in 2021. I’m excited to get in touch with nonprofits. I think what keeps up my drive is that my own processing of experiences and feelings will help someone else process theirs. I believe in the power of storytelling.

![image0[5426]](/x/lc-content/uploads/2020/10/image05426.jpeg)

Read more about The Origins of Kim and Kang at: https://www.kimsandara.com/

Do you have any advice for Queer POC artists growing up with a similar experience to yours, coming to terms with their own identity?

It’s going to be harder for Queer POC to thrive being creative, because you’re a little more vulnerable than everyone else.

Although it’s going to be harder for you, exhaust every resource that you can find to its limits, and keep yourself versatile in the things that you are able to do. Use those skills to the best ability to take care of yourself. When you take care of yourself, that’s when you have that nest to be able to create anything. I think the struggling artist trope for me is so tiring and I hate hearing it, because I don’t think it’s worth struggling to survive. Artists need to create. You have to take care of yourself so you can create. You can’t be sleepless and hungry while creating, nothing good will come out of that.

Despite the hurdles, your voice is needed. It might take a longer time to get an audience but when you reach one, there are people waiting to resonate with your story. It’s really important for us to see each other in our work to support each other, as a community. It’s important to connect with others and to genuinely build mutually supportive bonds. I think that community keeps us safe. I know whenever I’ve been in trouble, the community has always been more reliable than corporations, or things that are supposed to protect you, but don’t.

That’s all the questions I have for today, thank you for speaking about your work!

All images in this interview are courtesy of Kim Sandara. To see more of her work, visit: https://www.kimsandara.com/

This interview was conducted by Iona Nave Griesmann, an Intern at VisArts and current Illustration/Graphic Design student at Montgomery College. Their illustrative work can be found at @Iona_Nave on Instagram.