Interview with Edgar Reyes

Fragments

Edgar Reyes is a multimedia artist based in the Baltimore and Washington D.C. area.

For an introduction, would you please expand on your artists’s statement?

So my art practice is really centered around my own experience of growing up in the DMV area. Mostly diving into my relationship as an undocumented student and the relationships that I’ve had with my family members as they relate to migration and displacement. So, my work has a lot of emotional connections and sentiment behind it, as well as a lot of beauty. And that’s what the show is really about, highlighting those emotional, but also beautiful things that come out of stories of migration. I think just in general, my work really speaks to the historical reasons for who I am and how that relates to the way people view me, and why I exist in the spaces that I do.

Why did you decide to title your show Fragments?

I think fragments for me is really just relating to the way that memory is ephemeral, the fact that it’s free flowing and everybody’s experience is very different in the moment. As well as this idea that we only share a space with people for a moment in time. And it’s those fragments of time that really make us who we are, paired with the concept that we carry generational trauma and generational memories. So this idea of fragments is all these layers that make us who we are. We’re not just one thing, we’re all these fragments of things, along with experiences that didn’t happen to us from our past generations and the people who came before us.

I know that the majority of images in your show are pulled from family photos or your own personal archives. I was wondering if you would talk about some of those images and the stories behind them, along with the ways using a personal archive fits into your practice?

I think as an artist, there’s a sense of privilege, even saying “I’m an artist” carries a lot of weight. So, I think it’s really important for me, for lack of a better word, to be my own family’s historian. What I’ve taken on as part of my journey is to really look at my family and ask, what are they photographing and why? What are they keeping? And my grandma whenever I go visit her, I always pull out the top drawer of her dresser where there’s a whole array of photographs that she has kept over the past 20 to 40 years. It’s really beautiful just to see those little mementos, sort of relating back to the title, those moments that she’s kept.

And what you see in the gallery, are pieces of that, but also some photographs that I’ve been fortunate enough to take as I’ve been able to travel back to Mexico and visit family. So it’s a whole mixture of documenting both what my family has kept up, but also documenting my own journey of being able to go back, and being able to reconnect and breathe that air again from where I’m from. But also a place that I have mixed feelings about whether it’s home or not, because I’ve lived in the U.S. for so long. I think to answer that, I think the imagery really is about documenting my family’s history and showcasing or highlighting the journey that my family has taken in various shapes, various forms, in a beautiful light. When people hear of migration, or just hear of people that have been displaced, pain is often centralized, and I’m showing that, but I want to show it in a beautiful way.

I’m curious if the works on the pedestals are mostly composed of found elements or if they are pieces that you’ve sculpted? Why did you select those objects and what are the stories behind them?

So, there’s a few different sculptural elements that are part of the show. And I’ve been playing around with this idea of these concepts that I have included in the fabric pieces along with the sculptural forms. For me it’s part of documenting my family’s history, while also looking at the historical relationship of what’s happening around the world during the time that is being referenced in my family’s images. How has my last name come into existence? How have my family’s beliefs come into existence? And religion has played such a vital role in that, along with agriculture and what we eat, what we consume, how we make a living, that’s all intertwined. So, these sculptural forms are speaking about that specifically. There are sculptures of the Virgin Mary all throughout the gallery, all the sculptural elements that are dipped in black, and they’re just kind of silhouettes all throughout the show.

And those are a reference to many things, both growing up in a single family household, as well as an homage to the women who play such a vital role in our family, while also critiquing the role that Catholicism has had in shaping some of these negative stigmas that exist within my family. As you notice throughout the whole gallery, there are hints of some of that indigenous, spiritual essence. Some of the figures, one of them is a depiction of the Aztec god and she’s the only piece and the only idle there, that’s not dipped in black.

And I really wanted to highlight the fact that in Mexico, Catholicism has kind of co-opted some of those beliefs and reshaped them and, for lack of a better word, colonized the people from those regions. So it’s both an homage, but also a critique on the role that our beliefs have had. And then throughout the rest of the sculptural elements, I’ve some other mementos from my travels.

For example, the Aztec figure, that idol, was from my first time ever visiting some of the ruins right outside of Mexico city. And my emotional connection of being there, and existing in that space.

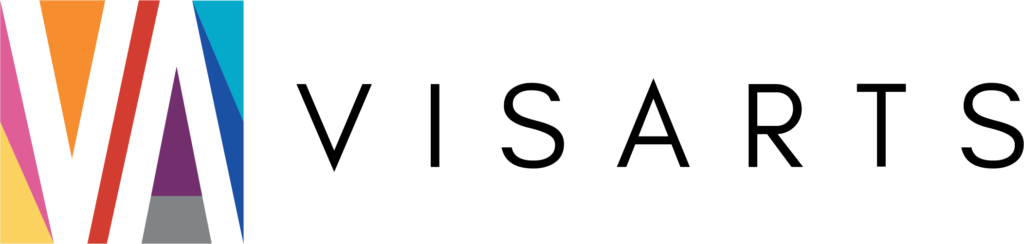

Then there’s another piece, that’s a purple maize, a purple corn. That’s wrapped with a chord you would wear to remember an idol or a specific Saint from a region. The Saint that’s depicted on the fabric is the Virgin of Talpa, and on the other side is an image of Jesus. So, it’s something that you would wear on your neck, but it’s basically choking that indigenous corn, and kind of stripping it away. And it’s speaking to, at least with my family corn, cultivating those lands has been a way of life, but religion has played such a big role in that, even though it’s an indigenous food.

And it’s just interesting for me that the Virgin of Talpa, even her origin and story, when she came into existence as an idol in that part of Mexico right outside of Guadalajara, she was made in an indigenous way. She was made using corn husks and papier-mache, that’s her original form existing in that indigenous space. So again, relating back to all the other sculptural forms that exist in the show, they’re all intertwined. It’s like a modge-podge of history that’s both known and not known, but is clearly there if you do the research. And I think, for me, it’s really important to not put it in people’s face, but in a subtle way, kind of submerge that history there. My goal isn’t really to force people to see those things, but just to realize that history is always there. If you look for those connections, with religion and the role that religion has played in undermining some of those indigenous beliefs that thrive, especially in my family. It’s pretty remarkable how we don’t really have a direct paper trail or association with a particular indigenous community. But what we eat, the language we speak, it’s a whole mixture of both Spanish and Nahuatl, and even some of the medicinal uses for plants. It’s pretty remarkable, the more I discover those realities are present but not there at the same time.

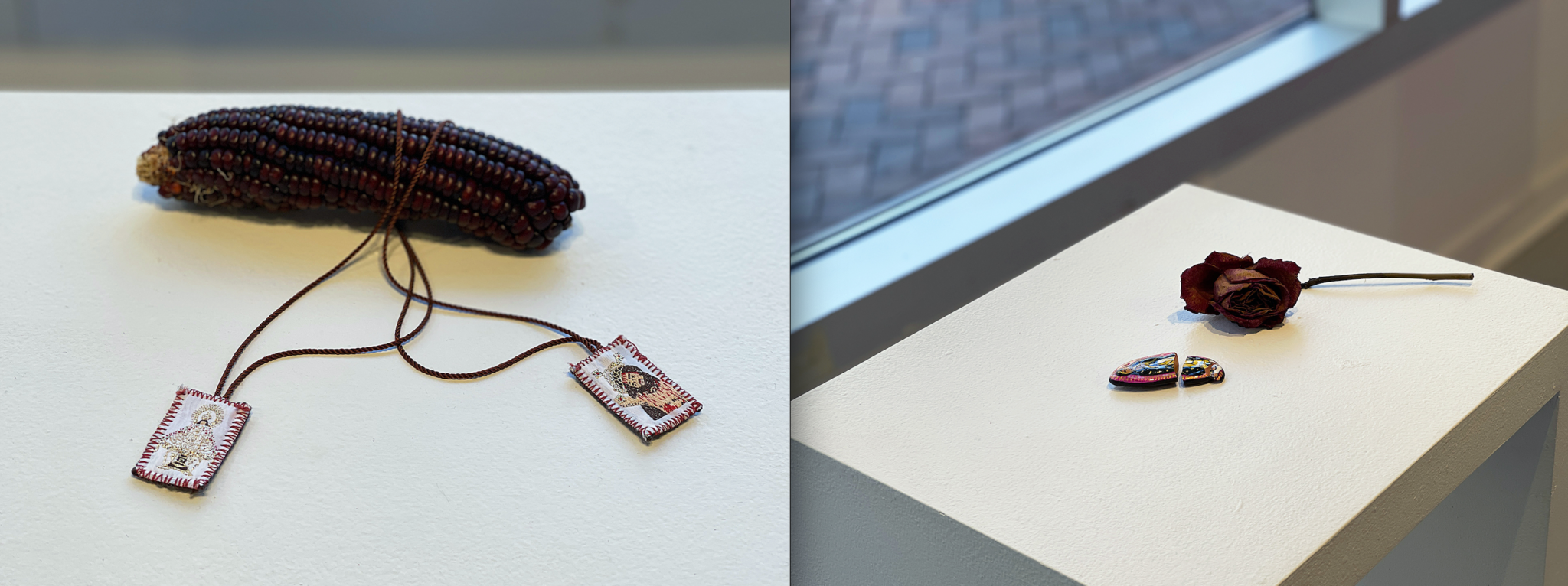

I think with my family, I’m always trying to find that balance between being respectful but also critical. Especially with religion, I still honor and respect the Virgin Mary as the patron Saint of Mexico. For a lot of people who migrate to the U.S. she’s somebody who they look for for guidance and for hope. But one of the pieces on display, it’s her but she’s broken, and she also has a rose next to her, but the rose is completely like dried out. I’m still unpacking what the meaning of all of the work in this show, but the ideas I’ve been talking about are definitely present.

I’m curious too about why you decided to dip the Virgin Marys in black paint. Was that just for uniformity, or what was your thinking behind that?

Yeah, I think that’s a good question. Why are they dipped in black? I think at least for me, from my biased belief, when you look historically at the connection between some of the indigenous spiritual beliefs in Mexico, prior to colonization, they kind of line and sink with what contemporary is there, but I think it’s all been whitewashed in a sense. So I’m kind of reclaiming that by dipping them in black, and reclaiming them back to the earth. A lot of those idols that you see in museums that were from Mesoamerica, some of them were either purposefully used as building materials for buildings that we see now, like churches or government buildings, or even some of the indigenous communities themselves submerged them underground so they could be preserved, to hide them.

But also, you know, how did I acquire these things? Goin to thrift stores. (laughs) I’m just imagining older white women also being the ones that are donating them. So I think for me, it’s really important just to reclaim these pieces, respect them for what they are, but also kinda kind of reverse it. I’m gonna co-opt what was co-opted in a sense.

Also in Mexico, the Virgin Mary, one of the things that I find really odd and beautiful but very puzzling, is that she’s seen as our black queen. When you look at Catholicism throughout the rest of the world, she’s depicted as a very pure white presenting idol. So, I think there’s a sentiment towards blackness and indigenous roots. That’s kind of the long but short answer, I guess.

That’s really exciting, you gave me chills just thinking about people burying things underground to preserve their history.

Yeah, it’s just nuts for me. People always say that history is told from the people that can tell it.

It’s really intense for me to read books, and look through images, and read experiences from the people who know that a piece has been hidden there for hundreds of years. And knowing how opportunistic people were, especially during the Mexican revolution, during the twenties and thirties, strategically knowing that they could leave Mexico with these sculptures. So, there’s lots of museums, especially here in Maryland, that have acquired these hidden gems from various communities, because they were very opportunistic, but not so much for the community that they were bought or taken from. So yeah, it’s bone chilling when you read that and you discover that you’re like, wait, when is the year you acquired this, the 1920s? Oh yeah so Mexico was a whole array of civil unrest, and because the government was dealing with civil unrest due to uprisings within major cities, they didn’t really care what was leaving or entering their borders. So, national treasures were leaving Mexico, which is nuts to me.

So that sort of leads to my next questions, listening to you talk about institutions owning things from other cultures. You show in so many different spaces, like at the Walters in Baltimore, you show at nonprofit arts centers, and then you also show in public spaces. I’m curious about what you’re thinking about as you’re navigating those different physical spaces and maybe what changes in your work as your navigating different spaces and institutions?

Yeah. I think the role that institutions play, influence what I show and how I show it. It’s a case by case basis, I think within public space it’s really important, especially if it’s a mural or if it’s a collaborative piece within a community, the community’s input is really important for me. Even if it’s not people helping with the design, I at least want to get their feedback and their input, in an attempt to help tell their story. And for me, when I go into community spaces like nonprofits, it’s kind of the same case, I try to be vulnerable, and accept that I’m not really there to represent the community, but there to help tell a story, or preserve something that the people in that community might find meaningful.

I’ve been really fortunate to be invited into different spaces, into different non-profits. But also, as an artist, I think it’s really important to tell your own story. And I think that’s definitely what this show is about, is telling my story. But still, I think it’s important when you go into institutions, to then ask yourself, why am I being asked to exhibit here? Why am I showing my story? What role do I play in telling my story? And then how can I continue to use that to my advantage? Not to purposefully make people uncomfortable, but to have conversations that are necessary for growth, both for myself, for the organization, and to make people feel welcome in that space. I think that at the end of the day one of my goals with my work, is to make and preserve stories, but also to create spaces where people feel welcome and seen.

I’m hoping that as people see my work, especially with this new body of work, people start seeing kind of that connection our life journey. Even though we might be from different parts of the world, or even if we’re neighbors, our life experiences are very similar, despite maybe language barriers or cultural barriers, we’re all dealing with traumatic things that, we sometimes don’t have control over, but we do have control over how we react to our differences.

Great. Thank you. That can be a really loaded question, so I appreciate your response. Now, back to your show. I’m curious about why you chose to work with fabric, instead of working on stretched canvas or on paper?

I think I’ve been really trying to figure out what the best medium is for me. And I think textiles are speaking to me in terms of the history of garments and the history of colors. I think that all intertwines with displacement, why people have been colonized in different areas, why different people have been displaced, or enslaved. For me, fabric has been a very versatile way to be able to share ideas on a large format. I’m also really obsessed with the translucency of some of the fabrics, like the chiffon pieces, relating back to kind of the idea memory and how memories are very free-flowing. We sometimes create false memories as well.

So, those chiffon pieces are where I’m really falling more in love with fabric, and this idea of layering things and being able to manipulate them. I think the show at VisArts really gave me the opportunity to see and further explore using fabric. I’m not a textile artist by any means, I’m not hand-making these, I am doing digital collages and then getting them fabricated. I think there’s something there as well, in different areas of the world, these indigenous ways of creating the fabrics really fascinate me. Eventually I really want to dig into that, but for now these pieces are a way to explore my history and the ways fabric and color play a vital role in the way our world is shaped.

I was excited by the way that you utilized the gallery space, floor to ceiling. There was one day after you had just finished installing, and I walked into work, and the pieces were like sails blowing around and it looked almost surreal, it was like walking into a dream. I mean, how often do you see an exhibition move like that if it’s not video projections? It made me think about how what’s left behind from family members is often dresses or garments and quilts, instead of family photographs.

Yeah. And I think even bringing up this idea of dreams, I think for sure that relates back to the title, these fragments. Even now I think looking back at traumatic experiences that I remember, or just memories that I have, sometimes it’s hard to tell if it was a dream or reality. Even when we deal with dreams, we sometimes wake up really upset, and sometimes it’s with loved ones and sometimes it’s with yourself and you’re really confused. I think that’s a really beautiful way to describe those fabrics. It’s very dreamlike, and the space was asking to be used in that way. And I’m glad that it happened unintentionally, but very organically as well.

And the idea that you said, of not having many things passed down from your family. I think, even when you’re moving, even if you’re volunteering to move, do you get rid of stuff and keep the most important things? And I think people, even now with COVID, are really becoming more aware of the significance of little moments and the significance of touch, the significance of hugging and kissing and being able to see people in person, and those are shared experiences. And now hopefully people will build more compassion for the experiences that I’ve had with family members and loved ones. People in my family have passed away and we haven’t been able to see them.

And the documentation, it’s just crazy, I keep trying to get my grandmother to give me a picture. She says, no, you can just take a picture of the picture. But these polaroids are falling apart, if I don’t take a picture now, you’re not gonna have anything later. So it’s been interesting, this idea that maybe my kids or maybe me and a couple of years, they’re going to have that experience of going through my grandmothers stuff and seeing those pictures, because those images are not archival, especially the polaroids she has kept. It’s been about twenty years, and they’re holding on for dear life and they’re all cracked and the emulsion is barely there.

Thank you for talking about your work in relation to the pandemic, I think other artists need to hear that insight right now. The last question I have is related to a particular piece that stood out to me, the image of a girl or a young woman with the braid standing in front of a white background. Most of the works are uniform in color and layering, but this piece seems to take on a different aesthetic. I was wondering if you could talk about that piece a little, or if there are any other specific works you might like to speak to?

A lot of my work is digital collage pieces experimenting with color and overlays, and just playing around with some of my own photographs. Something that I’m trying to become more comfortable with is just sharing the images as they are. Especially some of those very intimate images where I don’t have to alter them, they’re beautiful as they are. There are hints of that throughout the show, and I’m glad you pointed it out. Some pieces are just photographs printed on fabric, but that one particular piece is actually my youngest sister, and she’s kind of looking at her history in a sense, she has her back to the viewer and she’s looking towards the gallery.

So she’s looking at that generational history, and that entire exhibit is actually three generations. It’s my grandparents from my mom mother’s side, my mom and myself, my stepdad, my dad, in that space as well. What does it mean to be able to share and tell stories across three generations and to create work about three generations? I think it’s really important to kind of showcase that, most of the exhibit is dealing with different journeys throughout our different unique lives. There’s the one that you were mentioning with those larger chiffon pieces that are just free flowing. That’s kind of my grandparents’ journey of being together, then separating, continuing their lives and doing their thing.

I mean, I could spend all day talking about it, but most of the entire exhibit is just digging and unpacking, at least for myself, what does it mean to share and create work about the current three generations that are existing with my family right now? And there’s a fourth generation already, my grandparents have great-grandkids now. Hopefully somebody else can start creating and asking, what does that look like and what does that mean? Hopefully more inclusive, hopefully more happiness.

To see more of Edgar Reye’s work, visit reyesedgar.com

This interview was conducted by Megan Koeppel, the Exhibition Programming Coordinator at VisArts.