Interview with Aaron Maier

VisArts Next Generation Studio Fellow

By Iona Nave Griesmann

Aaron Maier is a Latino visual artist born and raised in the Maryland suburbs of DC. He obtained his B.F.A. from the School of The Art Institute of Chicago, attended the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, and has exhibited at the Queens Museum in New York City, SculptureCenter, The National Arts Club, The Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, and the Washington Project for the Arts. Aaron lives and works in Washington, D.C.

What are you working on for VisArts? Do you have any goals you would like to achieve during your residency?

Right now, I’ve been doing a lot of ink drawings and paintings. I came here with this idea that I was going to try something a little bit different from what I’ve been doing in my other studio at home. It’s opened up my practice a lot more because the ink by nature is very fast. Once you put it down, that’s it. And the newsprint is not precious, so I’m just pushing ideas out. So that was kind of my plan. To make a lot of work that felt raw and unfiltered, and then to see what’s there.

Why do you employ cartoons to illustrate your stories and ideas, and how does cartoon symbolism amplify the meaning of your work?

There’s an immediacy to them, and I can paint in a very observationally realist sort of way. When I’m working, I’m thinking about my feelings, and I’m thinking about things that give me something profound, so I start with something that’s very intense. To me, a cartoon is the quickest way to portray that onto a piece of paper.

If you’ve ever drawn something in Pictionary, you have a timer and you just have to draw as quickly as you can. I find that when you are working in this sense of immediacy, things come up that you weren’t even anticipating because you’re so directly involved. You just happen upon these things. And they’re yours, they’re gifts.

I think cartooning amplifies the meaning of my work by being very distilled. If you look at the use of cartoons or abstracted things, you get something that is very specific without being loaded with other things. In everyday life, if you look at a bathroom sign, its very clear that the icon is a type of person, whether gendered or non gendered or somebody who’s disabled. That’s the main point. So I just want to be very specific. I have these complex things that I’m uncomfortable with, but I want to be as clear about them as possible.

I think cartooning in a way, opens up my work. I don’t take it seriously when things are cartoon. I don’t struggle as much to find different ways to pull ideas of judgement on what art needs to be, or what my art needs to look like. I just respond directly to what I’m making, and that’s usually more authentic.

Corte Militar, 22 1/4 x 30 inches

Your mark making is noticeably distinctive and expressive. Do you seek to portray different emotions or themes using different kinds of strokes?

I think it’s an intuitive response. The more warmed up I am with my hands, the more controlled my marks tend to be. I’m also trying to emulate what my relationship is to whatever I’m drawing. Usually that happens with the type of mark I make, whether it’s the pressure, or the length of the stroke. If I’m drawing something and I want to be sort of romantic about it, my strokes are much longer and light. If I’m feeling angst, or some kind of convoluted feeling, then they’ll be a little more scratchy.

And it depends if I’m drawing something like flowers, and how I feel about a particular petal, or if the stem feels kind of bold, rigid or feeble. I’m responding with marks, and trying to use that amount of pressure in a way that I interpret what I’m seeing. I want to bring my judgement of the object, and the way something feels visually into the work.

Your artist statement reads that your work is influenced by the works of Chicago Imagists such as Barbara Rossi, Roger Brown and H.C. Westermann. What about their work inspires you, and do you employ some of the techniques they use in your own work?’

I studied with Barbara Rossi, and I really like H.C .Westermann’s and Roger Brown’s work.

What gets me excited about a painter is when I see something that I haven’t seen before or didn’t feel was possible, and I’m like “Oh, you can do that?”

When I was in art school I hated Cy Twombly’s work. It was scratchy, and it felt like “my kid could do that type of work”. But I pushed myself to really learn more about why that work was considered art, and why people actually said “No this is important!” It gave me a way to say “Well if everything and anything is possible, I can do anything.”

Roger Brown specifically has a very interesting way of creating clouds, landscapes and buildings that are so imaginatively unique. Like, he can do a building in the shape of a snake, and the clouds look like rocks in the sky, and it’s believable!

To see something impossible in artwork is exciting to me. It just adds to this validity of your own sense of weirdness. If you’re an artist who’s interested in weird things, then you give yourself more permission to explore and embrace that, which ultimately adds to this authentic sense of self within your work.

What experiences or questions did you have that helped you decide to center some of your work around memory, masculinity and race?

When I was growing up, my parents didn’t make a big effort to explain the whole problem of race in this country to me. Or gender for that matter. To me, two of the largest problems we face are patriarchy and racism, as systems that permeate through everything.

My father is white, my mother is Bolivian. I never felt like I fit in because my father’s side isn’t just white, they’re Jewish and Ashkenazi, so there’s a whole different layer of otherness in that. Feeling like an outsider, I wasn’t really sure of what artwork I wanted to make. I was really interested in conceptual art, but as a younger art student it was about proving something. Proving that I was brilliant. After listening to and reading about artists that I respected, everybody was pointing at the same thing, which was “you gotta get to know yourself.”

Fundamentally if I think about my identity, I’m half Bolivian, I’m half Jewish, I’m white, but what did that mean? All those questions became things that I needed to look into. Reading, therapy and talking to friends began to crack open these ideas that I really wanted to talk about.

My relationship with my father was pretty bad. I had a lot of abuse, and these very painful and sensitive things that happened when I was growing up. I would be making work in the studio, and would subconsciously keep going back into those ideas like a pattern. So in a way I realized what I wanted to talk about, but didn’t know how. Through therapy, looking at other artists’ work and embracing myself, I was able to decide for myself that these were interesting topics, and that I could talk about them in the way that I wanted to.

My work isn’t super direct but more subtle and nuanced, because that’s how I feel about my identity. I code switch a lot, play up my whiteness or my brownness to survive, to make friends, to find community,or to feel welcomed in spaces. I’ve done that without realizing since forever. Once I was able to think about these things concretely with language, and through painting about them, that’s when things became interesting and authentic.

When did you first discover that painting allowed you to access the psychological parts that were usually difficult for you to express?

I wasn’t happy with the work I was making. it was really conceptually driven,but it didn’t have much substance. It still felt very guarded and sort of dry. There wasn’t really me in that work.

So I started drawing. I took 8 ½ x 11 computer paper, and just doodled. This was a technique that I learned from Barbara Rossi back at the institution of Chicago, to take doodling seriously. So I just gave myself computer paper, ink, a pen, and just went at it. I made hundreds of drawings, sometimes when I should’ve been working. That gave me this big array of things to look at and think about. Then, I began to show them to people and ask them what they thought.

I then tried painting, although it was hard initially, because I made painting too precious, and drawings were always easier for me. It took me a while to get over that, and I was very awkward. I would build it up, paint over it, or I’d burn it or rip it up. It was painful, because I had not developed myself enough, and I wasn’t being patient with myself, I just wanted to be good.

I was too caught up in ideas about how to paint, and what to do. I didn’t have enough experience actually painting, or looking and thinking about mediums, and trying things out. It really takes a long time, and eventually you can filter out a lot of the stuff. An artist once said something like, “you turn on the faucet, and at first there’s brown dirty water coming out, until it clears and becomes clean”.

One painting I would like for you to talk about is ‘Dowlais Drive’. Is there a story that drove the creation of that painting? How does the imagery you use express the struggle of wanting love while feeling unlovable?

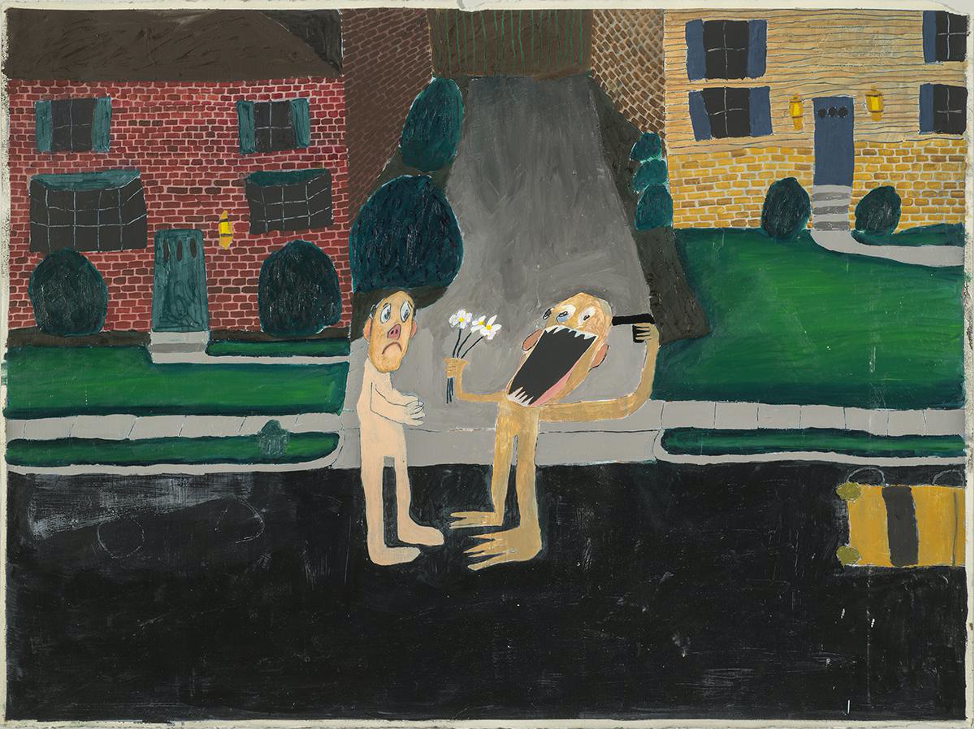

Dowlais Dr., 22 1/4 x 30 inches

So I painted this while I was at Skowhegan this past summer. I was feeling frustrated because I was in a new studio, and was feeling a lot of pressure to make something that proved why I was there. In that sense there was this sort of desperation. I thought about that desperation in a way that was isolated, and had the conclusion that one of my deepest fears was that I was unlovable. Based on personal history with my parents, not having my parents, an awful divorce and custody battle, my parents losing me to the court, and all this emotional baggage.

So this feeling of desperation was in full fling and I knew I wanted to make a painting. This strong image came into my mind of the house that I lived in with my father, and in that space came this feeling. Then I knew I wanted two characters, so I drew my dad and then drew me. I think I drew myself first, pointing a gun at my head offering flowers, and then I drew the other character, the response to that. In the image we are naked, because I wanted the focus to be on our bodies and the vulnerability of it.

I felt a deep empathy for myself in that moment, in this gesture of offering flowers and having a gun to my head, with this emulation of myself wanting love but also self loathing.

That contradiction also became my face showing everything out of whack, with everything like my teeth looking distorted. But I also wanted a sense of realism, so I put them in a solid space on the street.

That event never happened. I never had a gun, but that sort of feeling is definitely real. I think to me it was a very simple poetic way of describing the complexity of contradiction.

The next question is about your piece ‘La Mordida’. Can you talk more about the imagery and symbolism, as well as the tradition you chose to showcase in this painting? Does the cake covering the child’s face symbolize a sense of white privilege that your mom wanted for you?

Yeah it does. It wasn’t my intention at first, a friend actually pointed that out to me after I finished it. It was one of those things in which you get into something, and don’t realize that you are saying more honest and direct things without noticing. But yea, it is about this sort of contradiction, and I’m looking for that a lot in my work.

This one in particular portrays how you come to this country and want the best for your kids, but the problem is, that what this country considers desirable is based around white privilege. Does that mean we sacrifice parts of culture that aren’t as desirable?

La Mordida, 55 x 72 in

I think this question isn’t answerable in any easy way, but it’s something that every person of color ends up thinking about if they are participating in Capitalism, especially children of immigrant families. There is a big burden. My mom came to this country and she slept on a park bench in Dupont circle the first night. She didn’t speak the language and she only had 20$. I can’t just throw away all of that. I have to do something to show that this big gesture of leaving everything behind and coming to this country wasn’t done in vain.

It’s hard to decide and find that balance, to think about how you become affluent in this country without losing parts of yourself. Its tough because the more I looked at it, the more I learned about what whiteness meant, and how attached it is to class.

Throughout your career, have you made any significant discoveries about yourself that you now address in your work? Have you made any of these discoveries simply through the act of painting?

Yeah a lot of things. One thing I noticed was the conversations I have with people, because all that goes into the painting. The painting itself is just this the realization of these thoughts and things.

I’ve begun to think more about how in racial situations for example, white friends who don’t realize the things they say are racist or hurtful. And a lot of times I’ll be sympathetic, because they don’t directly experience racism in the same way. People don’t go up to them and say “Oh where are you from?” or “You cant be from the US, you look exotic.” These sort of things aren’t necessarily meant to be hurtful but end up hurting. Sometimes they’ll say, “That couldn’t have been racist.” and it’s like “You were but I get that you don’t realize that, because it doesn’t affect you.”

In a similar way, I’m looking more into my relationship with identifying as male, and patriarchal problems. I don’t experience the same transgressions that women do. I don’t get catcalled in the same way, I don’t feel unsafe when walking down the street, and because that isn’t my experience I am ignorant to a lot of my own behaviors that do occasionally transgress and offend women. They may not be blatant sexual assaults, but they’ll be things like, “actually, you’re kind of mansplaining,” or “ you’re talking over me”, and other things indicative of male privilege.

I understand in a similar way like how some white people don’t see their actions as racist, even though they are interpreted that way. If I don’t see how my actions affect somebody, it doesn’t mean that their reaction is not valid, it means that I need to pay more attention.

Fundamentally everybody has a right to feel what they feel, and their feelings are valid. So if I want to figure out ways to remove some of these society taught ideas that are hurtful, I have to pay more attention.

I think that painting has allowed me to think more critically about these things, and to spend more time studying them.

Thank you so much for speaking with us Aaron!

To see more of Aaron’s Work, Visit www.aaronmaier.com

This interview was conducted by Iona Nave Griesmann, an Intern at VisArts, and current Illustration/Graphic Design student at Montgomery College. Their work can be found at @Iona_Nave on Instagram.

This interview was conducted by Iona Nave Griesmann, an Intern at VisArts gallery, and current Illustration/Graphic Design student at Montgomery College. Their work can be found at @Iona_Nave on Instagram.